Missing a Direct Connection with American History

When you mention the name George Wallace to a person of a certain age, it’s likely to trigger one of a few thoughts or memories.

Maybe going to the University of Alabama to stop the school’s integration. Maybe the sadly infamous quote, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Maybe the memory of his attempted assassination, which left him in a wheelchair.

I was a bit too young to remember the first two, but I remember seeing clips on the TV news about his shooting. But after I graduated from college and dove into the newspaper business, I discovered a different side of the Alabama governor. More on that in a minute.

Over the past 15 years, I transitioned my home- and car-listening to Pandora, audio books and podcasts. Every now and again the radio gets tuned to NPR or some kind of easy-listening rock station.

But these days I find myself in East Tennessee, where I am having to re-tune my car’s preset radio stations. As one does, I started at 87.1 on the FM dial (although it’s not a dial anymore) and started scanning upward, punching stop when something interesting came on.

This is how I landed on a local sports-talk radio show, which is something that, in a past life, I would have locked onto immediately. The topic of the day was top football rivalries in the SEC. And, as it should have been, Auburn-Alabama was ranked at the top.

In the car, I nodded accordingly. Many people accept that notion as gospel. I don’t doubt it at all. One reason is George Wallace.

The sensibilities in Alabama

When I first moved to Montgomery, Ala., after college, I was introducing myself to several people on the beat that I would cover as a neophyte reporter. This is what polite young men raised in the South do — introduce themselves. Before the conversations ended, I was inevitably asked, “Are you for Alabama or Auburn?” This is a cliché, but it’s also true.

“Neither,” I said. “I’m from Tennessee.”

“So, you hate ’em both.”

“I just don’t care who wins.”

One fellow replied, “Well, it’s early. You don’t have to pick a side until game week.”

It was January. I laughed. He didn’t smile.

Nine or 10 months later, however, that feeling of importance came rushing back. I had weathered my start in Alabama’s capital city and enjoyed my job. I had new friends, most of whom were Alabama fans. I worked for an afternoon paper, The Alabama Journal (RIP), which meant that we put the paper out by 9 a.m. five days a week. The production part of my workday ended around 1 p.m. after the final edition was set to roll on the presses below. Often, however, the reporting and writing part of my day took place at night.

Chasing down a rumor

One Friday after deadline, I was in the office preparing to work that night and the following day. The phone rang. As the only person in the department, I answered it. The man on the other end had a question.

“I heard that Alabama suspended a player for tomorrow’s game? Is that true? Do you know who it was?”

No hello, no introduction, just a question.

“I haven’t heard anything about a suspension,” I replied.

“Well, can you check on it for me?” The man gave me his name. And then he said, “I work for Gov. Wallace, and he really wants to know if we’re going to be short-handed tomorrow.”

What?

Alabama Gov. George Wallace (bottom) meets in Selma, Ala., with Civil Rights leaders in March 1985 to celebrate the passing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Credit: Carey Womack

I was more than aware that Wallace had been brought back for a fourth term as Alabama’s governor. But I had no reference point that made me think he was an intense Crimson Tide fan. I guess I thought that, as a politician, Wallace had to walk a tightrope and support both Alabama and Auburn.

Nope.

I quickly scanned the wires and told the man, “I don’t see anything about a suspension.”

“Could you find out?”

“I’ll make some calls. Feel free to call back.”

I knew that any suspension would be a news story. And if we were the ones to break it around the state, it would be a bigger story.

Also, this was 1985, and now-legendary Alabama journalist Paul Finebaum’s radio show had yet to go national. If he even had one at that point. Otherwise, the man’s first call probably would have been to Finebaum, not some younger journalist who also hailed from the wrong state.

Ray Perkins tells (almost) all

I hung up and dug up a phone number for the Alabama football office, although I knew any call to Tuscaloosa on the Friday afternoon of a home game in Tuscaloosa was pointless. Coach Ray Perkins would be slammed by visitors coming by to glad-hand, and assistant coaches would be off recruiting. I knew I’d get to talk to a secretary in the football office, who was bound to take a message that would never get returned. (Yes, this was pre-cell phones.)

I dialed the number for Perkins’ office. To my amazement, Perkins picked up.

I identified myself and launched right in. “Coach, I received a call a little while ago, and the word is that you suspended a player for tomorrow’s game.”

“That’s not true,” Perkins replied. “I did not suspend a player for tomorrow.”

The way he said it made me think something was up. But what?

“Coach,” I asked, “did you suspend more than one player for tomorrow?”

“Yes, I suspended three players.”

Channeling Perkins’ specificity, I asked, “What three players did you suspend?”

He gave me the names of three good but not star players.

“What did you suspend them for?”

“Violation of team rules.”

“What rules did they violate?”

“I won’t go into that.”

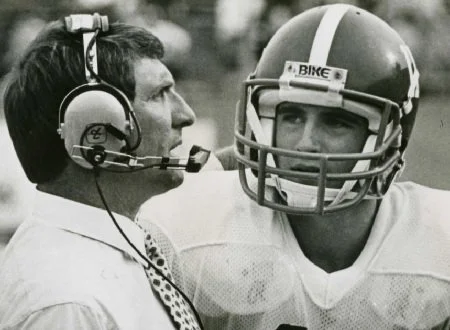

Ray Perkins (left) did not suspend Mike Shula. Credit: Paul W. Bryant Museum

Still suspicious, I asked: “Coach, did you suspend any more than three players?”

“No.”

“Did you suspend any players for future games?”

Perkins paused. “Now there’s an idea. Huh. I’ll have to think about that.”

I poked around the suspensions with a few more questions, but the coach had given me all the information he was inclined to. I thanked him for answering the phone and the questions and hung up.”

Sharing the scoop with George Wallace

I wrote up a quick story for the next morning’s paper (it was also pre-internet) and told the night editor about it.

As I packed to go home, the phone rang again. It was the tipster.

“Did you hear anything? The governor is beside himself. He knows it’s true.”

I gave the man my news and made him promise not to call The Birmingham News or Huntsville Times.

“All we care about is The Advertiser, but that’s you,” the man said. Kind of. The Journal and the Advertiser operated under the same publisher.

He was relieved that neither quarterback Mike Shula nor linebackers Derrick Thomas and Cornelius Bennett had escaped Perkins’ discipline.

“This will make the governor happy,” he said. “What’s your name again?”

Unfortunately, I didn’t think about it until after I hung up the phone that I realized I’d blown an opportunity. I should have withheld my information from my tipster so that I could deliver the information to the governor himself over the phone. I would have loved to hear his accent and ask about his love for Alabama football.

At that point in his life, Wallace had rejected the racist policies of his past as he worked to rewrite his legacy in his last act as a politician. He didn’t run for re-election the next year and was succeeded by Guy Hunt, the state’s first Republican governor since 1870.

I was too green to consider the fine points of the ethics of the situation. I probably shouldn’t have surrendered the suspension details to him. Then again, without him, I would never have known about the suspension.

In the end, it was a quid pro quo — perfect for dealing with a politician.